One of my favorite comments on the

first post in this series came from Lyndall Linaker, an Australian museum worker, who asked:

"

Who decides what is relevant? The curatorial team or a multidisciplinary team who have the audience in mind when decisions are made about the best way to connect visitors to the collection?"

My answer: neither. The market decides what's relevant. Whoever your community is, they decide. They decide with their feet, attention, dollars, and participation.

When you say you want to be relevant, that usually means "we want to matter to more people." Or different people. Can you

define the community to whom you want to be relevant? Can you describe them?

Mattering more to them starts with understanding them. What they care about. What is useful to them. What is on their minds.

The community decides what is relevant to them. But who decides what is relevant

inside the organization? Who interprets the interests of the community and decides on the relevant themes and activities for the year?

That's a more complicated question.

It's a question of HOW we decide, not just WHO makes the decision.

Community First Program Design

At the

Santa Cruz Museum of Art & History, we've gravitated towards a "community first" program planning model. It's pretty simple. Instead of designing programming and then seeking out audiences for it, we identify communities and then develop programs that are relevant to their assets and needs.

Here's how we do it:

- Define the community or communities to whom you wish to be relevant. The more specific the definition, the better.

- Find representatives of this community--staff, volunteers, visitors, trusted partners--and learn more about their experiences. If you don't know many people in this community, this is a red flag moment. Don't assume that content/form that is relevant to you or your existing audiences will be relevant to people from other backgrounds.

- Spend more time in the community to whom you wish to be relevant. Get to know their dreams, points of pride, and fears.

- Develop collaborations and programs, keeping in mind what you have learned.

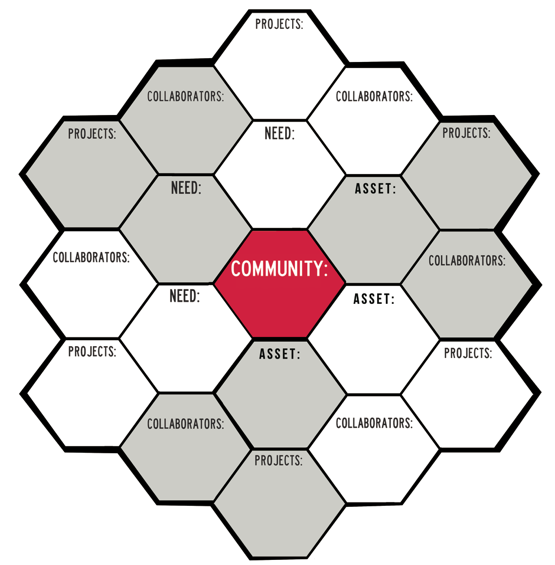

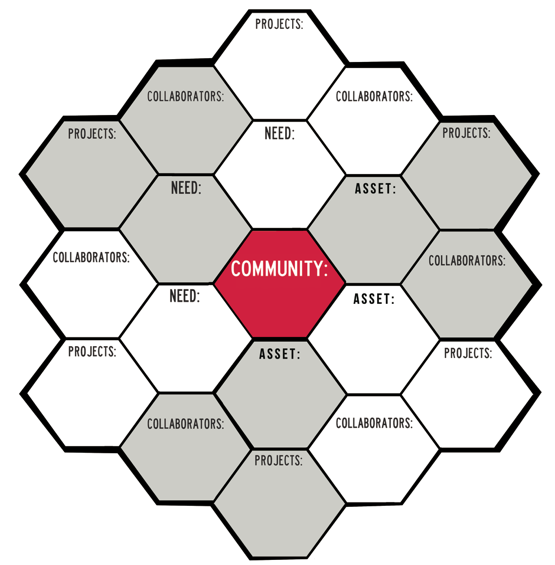

We use a simple "honeycomb" diagram (image) to do these four steps.

We start at the middle of the diagram, defining the community of interest.

Then, we define the needs and assets of that community. We're careful to focus on needs AND assets. Often, organizations adopt a service model that is strictly needs-based. The theory goes: you have needs; we have programs to address them. While needs are important, this service model can be demeaning and disempowering. It implies we have all the answers. It's more powerful to root programming in the strengths of a community than its weaknesses.

Once we've identified assets and needs, we seek out collaborators and project ideas. We never start with the project idea and parachute in. We start with the community and build to projects.

Here are two examples:

- Our Youth Programs Manager, Emily Hope Dobkin, wanted to find a way to support teens at the museum. Emily started by honing in on local teens' assets: creativity, activist energy, desire to make a difference, desire to be heard, free time in the afternoon. She surveyed existing local programs. The most successful programs fostered youth empowerment and community leadership in various content areas: agriculture, technology, healing. But there was no such program focused on the arts. Subjects to Change was born. Subjects to Change puts teens in the driver's seat and gives them real responsibility and creative leadership opportunities at our museum and in collaborations across the County. Subjects to Change isn't rooted in our collection, exhibitions, or existing museum programs. It's rooted in the assets and needs of creative teens in our County. Two years after its founding, Subjects to Change is blasting forward. Committed teens lead the program and use it as a platform to host cultural events and creative projects for hundreds of their peers across the County. The program works because it is teen-centered, not museum-centered.

- Across our museum, we're making efforts to deeply engage Latino families. One community of interest are Oaxacan culture-bearers in the nearby Live Oak neighborhood. There is a strong community of Oaxacan artists, dancers, and musicians in Live Oak. One of their greatest assets is the annual Guelaguetza festival, which brings together thousands of people for a celebration of Oaxacan food, music, and dance. Our Director of Community Engagement, Stacey Marie Garcia, reached out to the people who run the festival, hoping we might be able to build a collaboration. We discovered--together--that each of us had assets that served the other. They had music and dance but no hands-on art activities; we brought the hands-on art experience to their festival. They have a strong Oaxacan and Latino following; we have a strong white following. We built a partnership in which we each presented at each other's events, linking our different programming strengths and audiences. No money changed hands. It was all about us amplifying each other's assets and helping meet each other's needs.

Getting New Voices in Your Head

The essential first step to this "community first" process is identifying communities of interest and learning about their assets, needs, and interests.

How does this critical learning happen?

There are many ways to approach it. You can form a community advisory group. A focus group. Recruit new volunteers or board members. Hire new staff. Volunteer in that community. Seek out trusted leaders and make them your partners. Seek out community events and get involved.

We find that the more time we spend in communities of interest--hiring staff from those communities, recruiting volunteers from those communities, helping out in those communities, and collaborating with leaders in those communities--the easier it is to make reasonable judgments about what is and isn't relevant. It gets easier to hear their voices in our heads when we make a decision. To imagine what they'll reject and what they'll embrace.

If you want to make program decisions relevant to a group, the thing you need most is their voices in your head. Not your voice. Not the voices of existing participants who are NOT from the community of interest.

Here's the challenge: if this community of interest is new to you, it's hard to get their voices in your head.

It's hard for two reasons:

- If you are interested in being relevant to a community that is new to you, you likely have low familiarity and knowledge of that community's assets, needs, and interests.

- At the same time as you are learning about this community, stumbling into new conversations, your existing community is right there, loud and in your face, drowning out the new voices you are seeking in the dark.

Anyone who has been through a change process knows this. You start with the community to whom you are already relevant, with their peculiar expectations and strengths and fears. And then, you decide you want the organization to be relevant to new people. People with different expectations and strengths and fears. You learn something about these new people: they prefer programming later at night, they're inspired by this kind of program, they want content in this language. If any of these changes threatens the experience of the people already engaged, they may revolt. They may say you are dumbing it down, screwing it up, throwing the baby out with the bathwater.

It's easy to give up. It's easy to just listen to the voices already in front of you. To stay relevant to them and shed your visions of being relevant to more or different people.

But you can't give up. If you believe in the work of being relevant to new communities, you have to believe those people are out there. You have to privilege their voices in your head. You have to believe that their assets and needs and dreams are just as valid as those of people who are already engaged.

Every time an existing patron expresses concern about a change, you have to imagine the voices in your head of those potential new patrons who will be elated and engaged by the change. You have to hear their voices loud and clear.

These new voices don't exist yet. They are whispers from the future. But put your ear to the ground, press forward in investing in community relevance, and those whispers will be roars before you know it.

***

This essay is part of a series of meditations on relevance. If you'd like to weigh in, please leave a comment or send me an email with your thoughts. At the end of the series, I'll re-edit the whole thread into a long format essay. I look forward to your examples, amplifications, and disagreements shaping the story ahead.

Here's my question for you today:

Who decides what is relevant in your institution? Have you ever seen a project succeed or fail based on interpretation of community assets and needs?

If you are reading this via email and wish to respond, you can join the conversation here.

From 2006-2019, Museum 2.0 was authored by Nina Simon. Nina is the founder/CEO of

From 2006-2019, Museum 2.0 was authored by Nina Simon. Nina is the founder/CEO of